Conflict styles in context

24 May 2019In 2018 I took a course on conflict transformation, I wrote about why and how here. This third post explores how we can use different conflict styles in various contexts. It’s a long-format post so grab a hot beverage and get comfy.

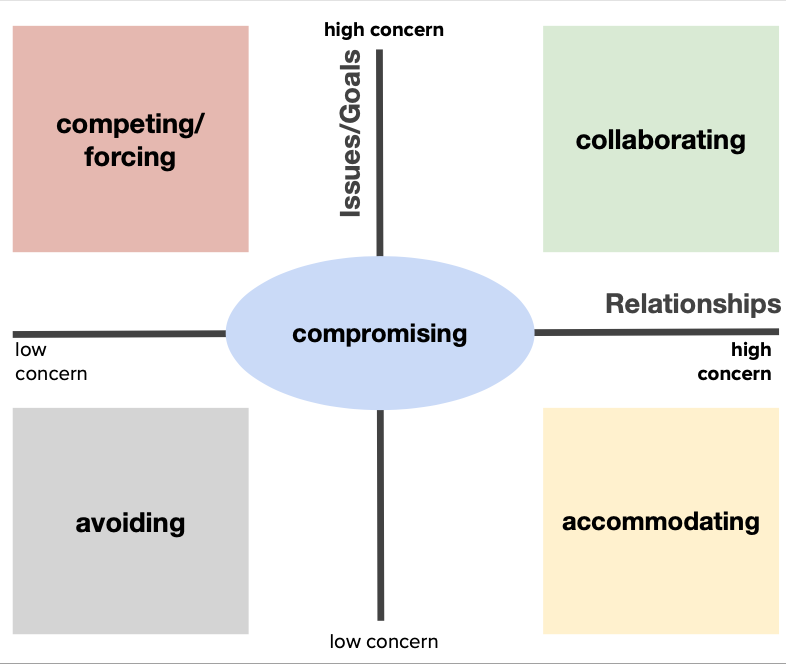

In the last post I wrote about the five conflict styles: competing, avoiding, accommodating, collaborating, and compromising.

We tend to default to one or two of these styles when we’re in conflict and don’t really think about what we’re doing.

Conflict transformation emphasises our ability to in fact choose a style based on the context of the conflict. Instead of defaulting to a preferred approach we can reflect on the context and make a more informed choice.

The two key contextual factors to keep in mind which help us make that choice are issues and relationships.

Thinking about issues

Issues are often at the centre of conflict, it’s the thing which we are in conflict about. These can be either the surface level issues which may have triggered the conflict or the deeper psychological issues which are fueling our strong reactions.

Issues can also be seen as goals or intentions. One of my favourite definitions of conflict is “two ideas sharing space, two intentions sharing space”. When our ideas or intentions feel in opposition to another person’s this can generate conflict.

In conflict, issues or goals typically exist on a spectrum of low to high concern: from “I couldn’t care less” to “over my dead body”. We react differently to conflict based on whether we view a given issue or goal with high or low concern.

Thinking about relationships

Another key contextual factor is relationships –– how do we relate to the person we’re in conflict with? How do we feel about them? Do we care about the relationship?

Like issues and goals relationships also exists on a spectrum of low to high concern. We don’t place as much concern on strangers as we do those we know well.

Power and social status plays an important role in where we place a relationship on that spectrum. When we’re in conflict with someone in power we sometimes treat that relationship with higher concern simply because of their authority.

Putting all it together

When we map the different conflict styles on an X and Y axis of issues and relationships we get an understanding of how the styles are used in context:

This diagram demonstrates both the behavioural patterns of when we gravitate towards a style and also how to choose what style to use based on the context.

When we feel more strongly about an issue than we feel invested in a relationship then we gravitate towards the competing style.

It doesn’t mean we don’t care about the other person. Sometimes it’s that in this particular moment this particular issue is more important to us than the relationship –– and we may believe the relationship is resilient enough to withstand the conflict.

In contrast, when we care deeply about our relationship with the person we’re in conflict with but don’t feel strongly about the issue, we tend to accommodate to their position.

On the other side of the quadrant, if we don’t care about the issue and don’t feel invested in the relationship we avoid the conflict. This can be a practical choice. However, it’s unusual for humans to be completely uninvested in our relationship with other humans (even strangers). More frequently we avoid conflict because it’s uncomfortable.

If we care deeply about both the issue and the relationship we move towards collaboration, seeking to affirm both our position and our relationship.

It’s empowering to acknowledge that a different conflict style works most effectively in different contexts, and that we can adjust the conflict style by emphasising either our connection to each other or clarify why an issue is important to us.

It means how we engage in conflict is a choice not a pre-determined fact.

When I feel defensive I do quick internal check: how much do I care about this issue and how do I feel about the person I’m in conflict with.

Depending on where I stand on the issue and the relationship, I’ll use the corresponding conflict style. If it’s something I care about and the relationship is resilient then I’ll stick to my position. If I don’t really care about the issue but I care about growing a relationship then I’ll accommodate.

Using this internal check has fundamentally changed how I interact with my teammates and improved my pairing skills. Where before I may have quibbled over some syntax for the sake of debating, I now recognise this as a low-concern issue.

It also means I’m better able at identifying how other people engage in conflict. I can respond with compassion and integrity, moving the conversation towards a compromise space by emphasising our connection with each other or clarifying the importance of the issue to each person.